Many people in the social sector hope that participatory grantmaking approaches can help transform traditional power relationships in the sector where those with the most money hold the most power. Our experience suggests that funders need to be more explicit about power and go beyond shifting who determines where dollars go.

Practices that seek to disrupt typical power relationships have grown in visibility and uptake over the last few years, including participatory grantmaking, which changes “the role of foundations from arbiters of what gets done to facilitators of a process in which they work with other organizations and non-grantmakers to designate priorities and act.”1 In 2019, Fund for Shared Insight launched a participatory grantmaking effort called the Participatory Climate Initiative. The funders were curious about extending the ethos of listening and feedback to organizations engaged in advocacy, building on prior work with direct-service nonprofits and a landscape scan from the Aspen Planning and Evaluation Program, “Meaningfully Connecting with Communities in Advocacy and Policy Work.” One of the explicit goals of the initiative included: “Experiment with participatory grantmaking to help elevate beneficiary voice and share power.”

Many lessons from the design and implementation of the Participatory Climate Initiative have been documented elsewhere, but as the evaluation and learning partner to Shared Insight, we had the unique opportunity to talk to those who participated. Shared Insight had convened teams to design the overall initiative and to make the grantmaking decisions. The teams were comprised of people from communities across the United States and Territories most impacted by climate change but least likely to be consulted on the philanthropic decisions that affect them. We asked participants for their responses to this prompt:

One purpose for engaging you is to shift power from funders to communities when making decisions about what issues are funded, how they are funded, and [how much to invest in them]. Tell us about your sense of power as a Design Team/Grantmaking Group member.

Those we spoke to appreciated the process and experienced different positive benefits from their engagement, yet they did not feel a shift in power, at least in the early stages of the work. The perceptions of members engaging in the design phase were accurate: Shared Insight’s plan was that the Design Team, as it was called, would be consultative, providing recommendations to Shared Insight, not making decisions. Though all of the team’s recommendations were adopted, which meaningfully shifted the scope and focus of the work, the power it held was intentionally and explicitly limited.

One of the recommendations Shared Insight adopted was to shift the role of the Grantmaking Group to be the actual decision makers about how to distribute the grant dollars. In the grantmaking phase, which followed the design phase, decisions were made by consensus among the participants who were not part of Shared Insight. It would be easy to think, “They made decisions about $2 million! Of course they had power.” What they told us in response to our question had many more layers, though.

I am still left wondering how participatory it is when there’s still a power imbalance at the end of the day – in terms of information of the long-term investment and impact the funders of these funds intend to have in the communities and peoples we are a part of and serving. The tables still seem pivoted in the direction of who has the most control of most of the resources.

People talked to us about the power they felt individually as trusted members of a process, the power they felt in community with others, or the inherent power they felt as members of communities already solving their own problems, with or without philanthropic support. They experienced positive examples of power in ways we hadn’t fully expected.

At the same time, akin to those in the design process, most of the people involved in the grantmaking phase felt that power hadn’t shifted significantly or enough.

While they did experience different types of power, participants signaled they knew that meaningfully addressing climate change and its impacts on communities would require more. They questioned the limitations they still had to operate within, such as not having enough money to really address the significant issues communities are facing and being confined to a more transactional, one-time project rather than being able to pursue change through ongoing relationships. It wasn’t that the power to make decisions about money didn’t matter, but that it wasn’t enough. The participants spoke about their interest in ultimately seeking collective liberation, which has been described as acting in ways that recognize that “all of our struggles are intimately connected, and that we must work together to create the kind of world we know is possible.”2

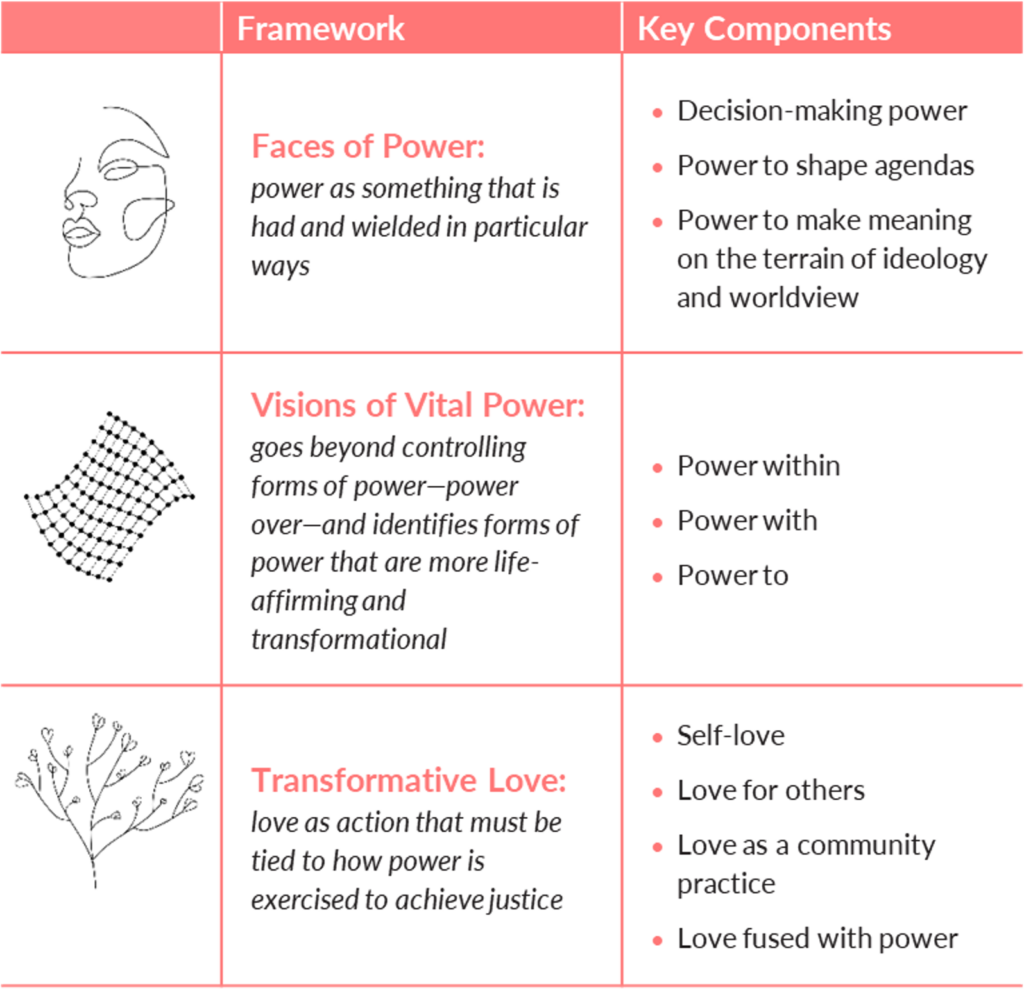

Our evaluation led us to realize that perhaps there were different frameworks for understanding power at play among the people involved, and that it could be helpful to explore these frameworks explicitly. We also recognized that we needed to more directly expose how white supremacy and colonialism shape the dominant mental models in philanthropy, even when there are good intentions to shift power. We found three different frameworks for thinking about power,3 as summarized in the table below. These frameworks are not mutually exclusive or exhaustive; they can be used together to understand, expand, and/or facilitate further conversation about what we mean by power.

Because our mental models define what we think is possible and up for debate, having a broader and more comprehensive set of ways to understand power can help funders and partners have deeper, more meaningful conversations about what is and isn’t on the table. If you think power is only having a seat at the table and making decisions about money, you’d have one perspective on participatory grantmaking. If you believe power should allow you to set the agenda and achieve transformative change, you would feel very differently. And no one framework is *the* answer — having a variety of ways to understand a concept like power can help us appreciate — and interrogate — the idea with more nuance and breadth. It also can help us be more honest and transparent about how power operates between funders and partners, including who gets to decide how power shifts and by how much.

Many people hope that participatory grantmaking approaches can help unlock some of the typical power relationships that exist in the social sector. Shared Insight’s experience and our work with the initiative’s participants suggest that funders need to get explicit about how they think about power, push themselves to think about power in broader and more transformative ways, and cede more than just the right to determine where dollars go.

Footnotes:

1Participatory Grantmaking: Has its time come? Accessed 062022

2Introduction to Collective Liberation Accessed 072622

3Richard Healey and Sandra Hinson, The Three Faces of Power (Mountain View, CA: Grassroots Policy Project). Available here

Just Associates (Written by Valerie Miller, Lisa VeneKlasen, Molly Reilly, and Cindy Clark). Making Change Happen: Concepts for Revisioning Power for Justice, Equality and Peace, 2006.

Shiree Teng and Sammy Nuñez, Measuring Love in the Journey for Justice: A Brown Paper.

About the author: Sarah Stachowiak, CEO of ORS Impact, thinks about how data, measurement, and evaluation can help clients learn and strengthen their work.