Staff at Natividad Foundation knew from the start they might have a rocky road implementing the Listen4Good client survey. Many patients at Natividad Medical Center are immigrants from Mexico who do not speak English, have low levels of formal education and literacy, and may not be familiar with the concept or practice of surveys.

Still, the foundation was committed to hearing from patients who access its in-house interpreting service, so it pressed ahead with translating and tailoring L4G survey questions. Among other changes, they substituted zero-to-10 answer scales, which are not widely understood among some Indigenous populations, with scales that feature pictures.

Working closely with interpreters, Natividad collected feedback from hundreds of patients, and, in response, tweaked and improved its interpreting program. For example, interpreters are now required to take an additional eight hours of training that covers issues related to customer care and workplace professionalism.

When it came time to consider how to close the feedback loop — report back to survey takers what they said and what the organization is doing about it — foundation staff felt a bit stumped. Many Indigenous languages have no written form, and low literacy rates in English and Spanish meant informational brochures or posters were out. Then, Natividad hit on the idea of making videos, something it had recently started doing to educate parents in the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit.

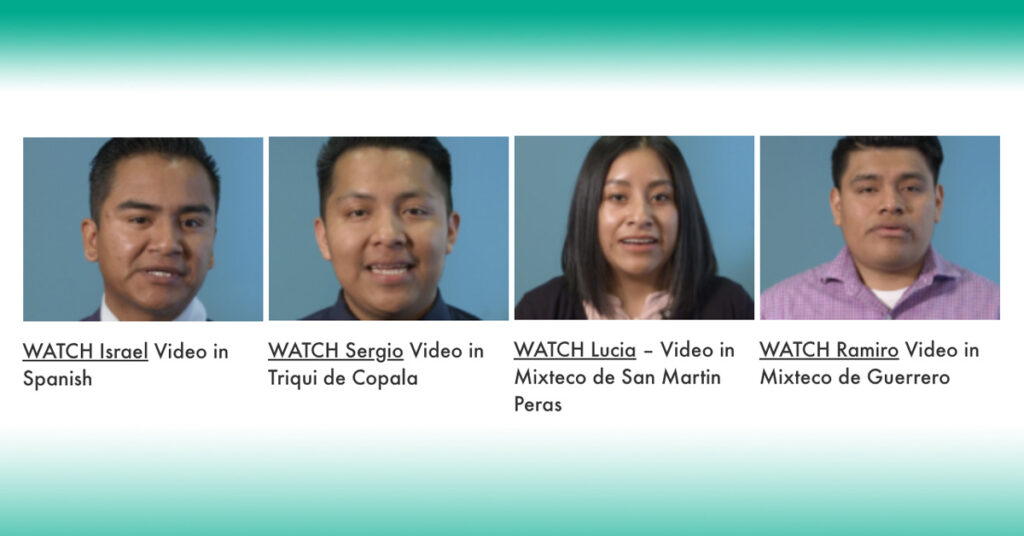

Working hand-in-hand again with interpreters, the staff wrote a script to be translated into Spanish and then into Triqui de Copala, Mixteco de San Martin Peras, and Mixteco de Guerrero, three of Mexico’s 68 Indigenous languages most commonly spoken among Natividad patients.

Israel De Jesus, an interpreter who helped with the videos and is featured in the Spanish-language one, says readying the scripts took about a week because translations can be tricky. Words including “satisfaction,” “mentality,” and, even “gallbladder” have no counterpart in the Indigenous languages, he explained.

But Natividad got it right. The videos, which are on its website and will be posted on social media and run on in-hospital televisions, have been well-received. They thank clients for taking the surveys, and tell them their feedback led to the additional training time for interpreters.

Israel showed the Triqui video, featuring his colleague Sergio Martinez, to his aunt, a Natividad patient, who told him that “it was great and she understood 100 percent.”

The best part, he says, will come when patients start seeing the videos on screens in the hospital.

People “will feel more welcome, more confident,” Israel says. “Now they’ll know we speak their language here.”